Editor’s Note: Douglas Brinkley is professor of history at Rice University, CNN presidential historian and author of the new book, “Rightful Heritage: Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Land of America.” The opinions expressed in this commentary are his.

Story highlights

Brinkley: Our national parks are falling apart because of underfunding

Congress should spend the money needed to preserve our national parks

On June 6, 1944, arguably the most momentous day of the 20th century, President Franklin D. Roosevelt refused to forget America’s national parks.

Just before 1 p.m. ET on that gold-starred afternoon, the entire world transfixed by the Normandy invasion, Roosevelt received the deed from the state of Texas that forever protected the 708,000 acres of West Texas mountain range, Chihuahuan desert scape and a maze of fortress-like canyons made by the Rio Grande.

Six days later, Big Bend National Park was established. (It has since been expanded to 801,163 acres.)

Not only was federal money poured into the Lone Star State to prepare Big Bend for tourists, but FDR also reached out to President Manuel Avila Camacho of Mexico urging him to follow suit with his own Rio Grande park. (Unfortunately, he didn’t.)

“These adjoining parks would form an area which would be a meeting ground for the people of both countries,” Roosevelt wrote to Camacho, “exemplifying their cultural resources and advancement, and inspiring further mutually beneficial progress in recreation and science and the industries related thereto.”

That Roosevelt didn’t back-burner the National Park Service with World War II raging, even urging Mexico to emulate Big Bend, should inspire Congress to act with newfound boldness and resolve in upgrading America’s priceless natural and cultural heirlooms.

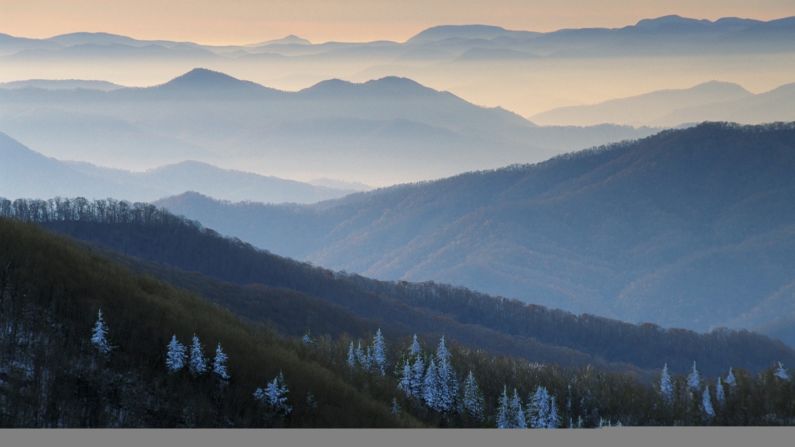

This August 25 is the park service’s centennial, a golden opportunity to address the maintenance backlog and chronic neglect that many of our National Parks are struggling with.

I recently visited Padre Island National Seashore along the Gulf of Mexico in Texas and was flabbergasted that structures have deteriorated beyond belief. The boardwalk needs immediate replacement. The law enforcement guard station that burned down a decade ago has to be rebuilt. The telephone system is kaput.

It is disgraceful that we treat this Texas gem, the longest undeveloped barrier island in the world, so miserably.

More from CNN: National Park Service Centennial coverage

Just as unloved is Fort Sumter National Monument, a sea fort near Charleston, South Carolina, which I also visited recently. It’s mind-boggling that this historical treasure, the spot where the Civil War began on April 12, 1861, has crumbling brick walls, broken-down sidewalks and chronic water seepage problems.

Even though Fort Sumter is a tourist-dollar mainstay of Charleston, we’re letting an intrusion of breakwater slowly turn the old fort into a quasi-ruin.

Our national parks are the envy of the world. And the superintendents and their staff are stupendous. Yet due to budget constraints, we’re treating these sacred places terribly.

Don’t we have an obligation to maintain Philadelphia’s Independence Hall and Mount Rushmore in South Dakota? Why are we allowing oil and gas companies to savage the badlands vista surrounding Theodore Roosevelt National Park in North Dakota?

In Everglades National Park in Florida, the Burmese python, an exotic invasive species, is estimated to be responsible for the 90% decline of small mammals in this fragile wetlands ecosystem. The park service needs more federal allocations to properly maintain our system. We need a modern-day Civilian Conservation Corps of young people to rid our parks of invasive species.

At nearby Biscayne National Park, also in Florida, the purposeful and accidental release of aquarium fish specimens is destroying native species. Another distressing problem is the coral reef dying at Biscayne and recent congressional votes to prevent the designation of a marine reserve for a fraction of the reef system in this popular park.

What point is there in establishing national parks — like the Everglades and Biscayne Bay — but not maintaining them and protecting the ecosystem habitat?

About half the park service’s infrastructure needs are for maintenance of park roads, including the Arlington Memorial Bridge connecting Washington. D.C., and Virginia and the Grand Loop Road in Yellowstone National Park.

100 years, 100 National Park Service experiences

At California’s Yosemite National Park, $80 million in emergency funds are needed to repair three wastewater treatment plants in El Portal, Wawona and Tuolumne. Sewage might overflow into the Merced River and Tuolumne River watershed if this problem isn’t addressed soon.

The 84,000 acres of water at gorgeous Voyageurs National Park in Minnesota are at risk due to nearby sulfide mining, according to the National Parks Conservation Association. The Environmental Protection Agency needs to ban these mining outfits from poisoning some of the most pristine waterways in America.

And Shenandoah National Park in Virginia needs an immediate $90 million to repair crumbling bridges and replace failing wastewater systems. And so it goes.

To be fair, sometimes the United States Interior Department has been its own worst stewardship enemy.

In Olympic National Park in Washington state, mountain goats were reintroduced in the 1920s. They have bred out of control, eating the high alpine meadows needed for marmots to thrive. One goat recently gored a hiker to death. (These goats need to be removed, which takes federal money.)

Worse yet, too often the National Park Service and US Fish and Wildlife, both agencies of the Interior Department, over-cooperate with nearby ranchers in the American West to the utter detriment of imperiled species.

In Yellowstone National Park, the Obama administration has mistakenly taken steps to undermine the grizzly bear’s federal protections under the Endangered Species Act. Bear trophy hunting on the edges of Yellowstone is now unconscionably allowed.

I recently joined a group of concerned citizens — including such luminaries as E.O. Wilson, Ted Turner, Terry Tempest Williams and Doug Peacock — who have pleaded with the White House to reverse the dismal decision.

We pointed out that Yellowstone’s bears are a remnant and isolated population. They must be allowed to wander safely outside the park without being shot willy-nilly. Americans would never permit hunting of America’s bald eagle. The casual killing of Yellowstone grizzly bears is equally deplorable.

But most of the park service’s problems come from congressional indifference. Due to funding shortages, the agency has a $12 billion backlog in deferred maintenance. That is a high price for sure. But to continue playing ostrich would be disastrous.

A bipartisan congressional coalition should spearhead a great national effort, with the help of Fortune 500 companies, to pay this bill off as the cornerstone of the National Park Service centennial.

Everybody is looking for the new moon shot that will unify our country. Helping preserve our treasured landscapes is both doable and meaningful. My vote is to bring the private sector and federal government into an unprecedented effort to expand and properly maintain our national parks and historic sites.

Back in 1940, FDR said it best.

“I see an America whose rivers and valleys and lakes — hills and streams and plains — the mountains over our land and nature’s wealth deep under the Earth,” he said, “are protected as the rightful heritage of all the people.”

If we really love our national parks, as millions profess on the eve of the centennial, then we need to care for them properly. To turn a blind eye on our own “rightful heritage” is a telltale sign of America — not just our national parks — in ghastly decline.